Ireland is an island nation located in the North Atlantic Ocean. Fluffy lambs on lush green pastures, cozy cities and ancient castles, the power of the Atlantic and friendly people – all this about Ireland, whose fabulous atmosphere penetrates to the bone.

Conference of Historians in Dublin

Date: August 23 -24, 2023

Address: 14 Main st Rathfarnham, 14, Dublin

Event historians will meet to discuss their research and experiences in Irish history. The meeting will take place over two days and will include presentations, discussions, and networking among historians.

The first day will begin with a keynote address from Professor Desmond O’Connor, who will talk about the significance of Irish history in world culture. This will be followed by presentations on various periods of Irish history, from the Celtic period to the present. Topics such as politics, religion, economics and culture will be covered to present a comprehensive understanding of Irish history and its impact on world history.

On the second day, historians will discuss their research and projects and their contributions to the field of Irish history. There will be discussions and exchanges among historians to understand what topics and issues are most relevant at the present time.

At the end of the meeting there will be a city tour so that historians can enjoy the beauty of Dublin and exchange impressions and ideas.

This meeting of historians in Ireland is a unique opportunity for historians and other scholars to exchange knowledge and experiences about Irish history. It is also a great opportunity for anyone interested in Irish history to learn more about the various periods of the country’s history and its impact on world history.

Conference program

Day 1:

9:00-10:00 – Registration of participants

10:00-10:30 – Opening and welcoming address by the organizers

10:30-11:30 – Keynote Speech by Professor Desmond O’Connor on the History of Ireland and its Impact on World Culture

11:30-12:00 – Coffee Break

12:00-13:00 – Speaker on the Celtic Period in Irish History

13:00-14:00 – Lunch

14:00-15:00 – lecture on the Middle Ages in Ireland

15:00-16:00 – Lecture on Ireland’s Modern History

16:00-16:30 – Coffee break

16:30-17:30 – Panel Debate: “The History of Ireland in the Context of World History

17:30-18:00 – Closing remarks of the day and announcement of the next day’s schedule

Day 2:

9:00-10:00 – Breakfast and free socializing

10:00-11:00 – Report on Irish History

11:00-12:00 – Lecture on Ireland’s Religious History

12:00-13:00 – Lunch

13:00-14:00 – Lecture on Ireland’s Economic History

14:00-15:00 – Presentation and discussion of historians’ research and projects

15:00-15:30 – Coffee Break

15:30-16:30 – Panel Discussion “Modern Problems and Challenges of Historical Science

16:30-17:00 – Final word and farewell to participants

17:00-18:00 – City tour for those interested.

During the historians’ conference in Ireland, the following questions will be addressed:

- What events and facts from Irish history have had the greatest impact on world history?

- What role did the Celts play in the formation and development of Irish culture and history?

- What was the role of Ireland in the history of Christianity?

- What challenges and problems do historians face in studying Irish political history?

- What is the role of the Irish economy in the development of the country and its relations with other countries?

- How is Ireland’s history reflected in the modern world and what are its prospects for the future?

- What is the significance of historical scholarship in today’s world and what challenges does it face in the context of a rapidly changing world?

- What opportunities are there for Irish historians to collaborate with colleagues from other countries and regions?

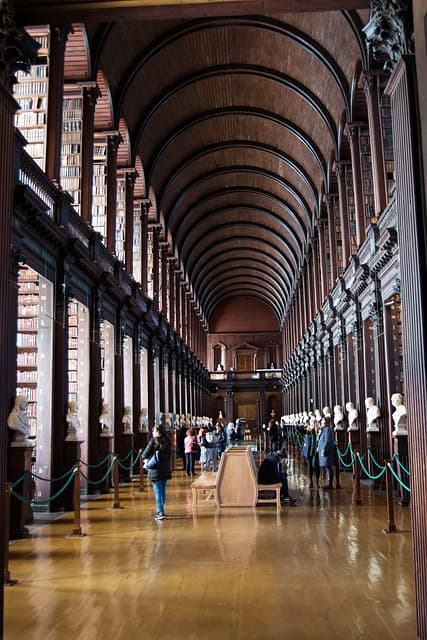

Ireland’s oldest educational institution, founded at the end of the 16th century, is located in the heart of Dublin and is called Trinity College. It is the place where such famous figures as Jonathan Swift, Oscar Wilde, Samuel Beckett and Bram Stoker spent their university days. The Trinity College Library is home to a gem and a shrine to the Irish people, the Book of Kell, written in the late sixth century. It is a richly decorated handwritten gospel, created, according to one version, by monks from the monastery of St. Columba on the Scottish island of Ayon.

Interesting Facts about Ireland

The Republic of Ireland (Republic of Ireland)

– is a separate state. In 1922 the Irish Free State emerged, which in 1949 was proclaimed the independent Republic of Ireland. In Irish the name sounds like Poblacht na hÉireann, which is often shortened to Eire. The capital of the Republic of Ireland is Dublin.

Northern Ireland

is an autonomous part of the United Kingdom located in the northeastern part of the island of Ireland. It occupies 1/6 of the island. The capital of Northern Ireland is Belfast.

Ireland has two official languages, English and Irish.

Irish is considered the first and national language, though only 1/3 of the population speaks it, but English is spoken by all.

Brú na Bóinne Brú na Bóinne

This is a complex of 40 burial mounds, which were built in the Neolithic period (2750-2250 BC). These mounds are 1000 years older than Stonehenge and 500 years older than the Egyptian pyramids at Giza.

Skellig-Michael

A rocky island cliff on which a monastery was built in the 6th century BC. It is one of the most inaccessible monasteries of that time, which is why it is well preserved.

Register now!

Award Winning & Certified!

Rainbow Riches is the most popular game based on Irish mythology: leprechauns, clovers and pots of gold. Bright design and thematic music. Try it too!

Attending a conference is a good way to enhance your understanding of history. Don’t let your homework stress you out! If you have inquiries for your history homework help or online option “do my history homework” you can easily find a suitable service. There are may resources available to help you in history field.

Check out a review of the best Irish casinos not on Gamstop here – from the best gaming experts in the gambling industry.

Unleash your winning potential at galera bet. Big wins and incredible rewards await for YOU!

Need a payday loan near you? Online payday loans at Payday Bears have got you covered. Our online payday lenders are available in your area, ensuring you can access the funds you need without any hassle. Apply now and experience the convenience of borrowing with Payday Bears.